In the last post, we covered the essentials that you need to get a Workflow (and your Response Group) up and running. In this post, we’ll cover the full seven steps to configure a Response Group.

Before we begin, a caution:

The Response Group Configuration Tool can hiccup every once in a while, especially if you are creating a number of Response Groups at the same time. I recommend that you configure the bare minimum of SIP Address, Display Name, and Queue, then hit save. Come back and edit the Workflow after that.

If you need to step away from the tool mid-build, or have configured some particularly cool and detailed settings, hit save often.

And lastly, you must have already defined the Queue that you will assign to handle calls. Saving after you configure the SIP Address, Display Name, and Queue will save you from getting to the end of the page, and doing a facepalm because you can’t save your Workflow config without a Queue to assign.

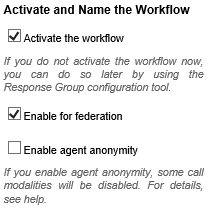

Step 1: Activate and Name the Workflow

Let’s break this one down into three areas.

The core of the Workflow

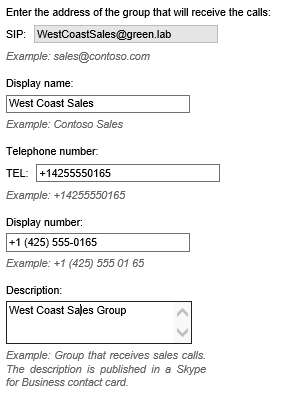

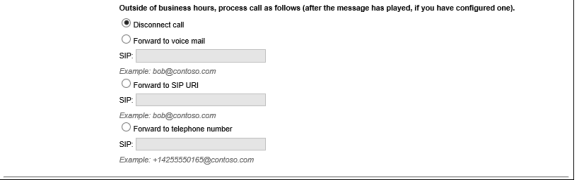

We covered SIP Address and Display name in the previous post. Telephone number is straightforward. Note the formatting here, they’ve included the tel: for you, unlike for user LineURIs. Display number should be the Telephone number, but formatted to however local users are used to seeing the number. Description is any text that you wish, and note that this text is published on the Contact Card for the Workflow object.

Workflow objects aren’t much different from user objects in Skype for Business from a contact list perspective. They are searchable, clickable, have contact cards, and you can add them to your contact list and favorite them.

Workflow Management

You have a managed or unmanaged Workflow. Setting a workflow to managed allows you to delegate the administration of the entire Response Group – Workflow, Queue, and Group – to one of more Skype for Business users. This is awesome, because it means that IT is no longer required to make every little tweak to the Response Group once it’s set up.

I think this is a terrible description of the function, because it affects Workflows, Queues and Groups.

Once you’ve delegated management of a Response Group, the manager can use the Skype for Business Control Panel and the Response Group Administrator Tool to manage things like Workflow hours, Queues and Groups, messages, schedules and IVR workflows – all the stuff that IT guys don’t want to do. They cannot create or delete workflows, or change the SIP address and telephone number – all the stuff that would break things that IT would then have to fix.

Note that when Response Group is set to Managed, the Queues and Groups cannot be shared with any other Response Group, even if they have the same manager. This makes a lot of sense, if one manager has created Queues for their business unit, another business unit manager shouldn’t be able to use or modify that Queue for their own purposes. You can assign multiple managers to a Response Group, if you need to.

The default is Unmanaged, which means that only members of the CSResponseGroupAdministrator group can create or edit Response Groups. It’s probably a bad idea to simply add a user like the manager of your account department to this group, it grants them too many permissions and then break all your stuff.

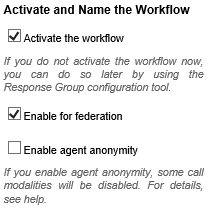

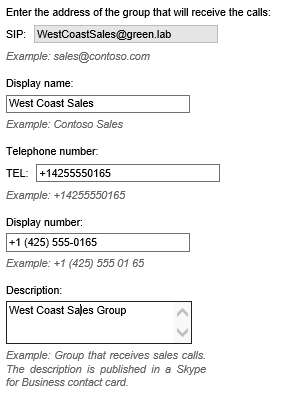

Activation, Federation, and Anonymity

Activation is straight-forward. Deactivating the Workflow means your Response Group isn’t going to take calls, but the number and configuration remain assigned. I use this often when I need to preconfigure a Response Group, but don’t want calls coming in to agents quite yet.

Turning Federation on means that users in Federated organizations can place a Skype call to the Response Group instead of needing to call via the PSTN. Since you can always call via the PSTN, turning this off offers no security benefit. If you do leave it on, make sure you test from a Federated client as well as the PSTN. I’ve seen some firewalls prevent a Federated caller from getting to a voicemail from a Queue timeout, but PSTN callers work just fine.

Enable Agent Anonymity is our last option. As the italic text from Microsoft indicates, this does limit some functionality. What it does do, is allow a user to place a call as the Workflow, so that their personal details are not revealed. This is great for helpdesk scenarios, where you don’t want people finding out how to contact your help desk staff individually and directly.

Gotcha! If a user is home on one pool, and a Response Group is on another, the Anonymity function is not available. The Skype for Business Windows client is the only client that I’m aware of that can do Anonymous calls – no phones currently support this function.

The limitations that Microsoft is referring to are minor for phone calls, and typically involve other modalities. For example, you can’t start an anonymous call with IM or video, you have to start with voice and then add the other modalities. If your goal was to have an IM session, it seems like overkill to have to phone the other person before you can flip IM on… Anonymous calls do not support conferencing, screensharing, file transfer, whiteboards, and recording.

Step 2: Select a Language

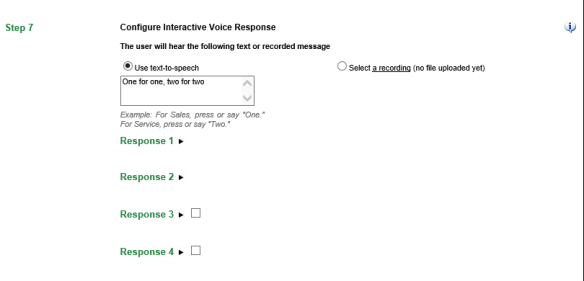

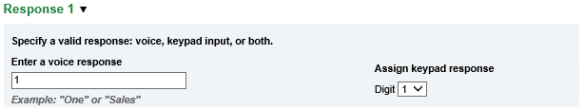

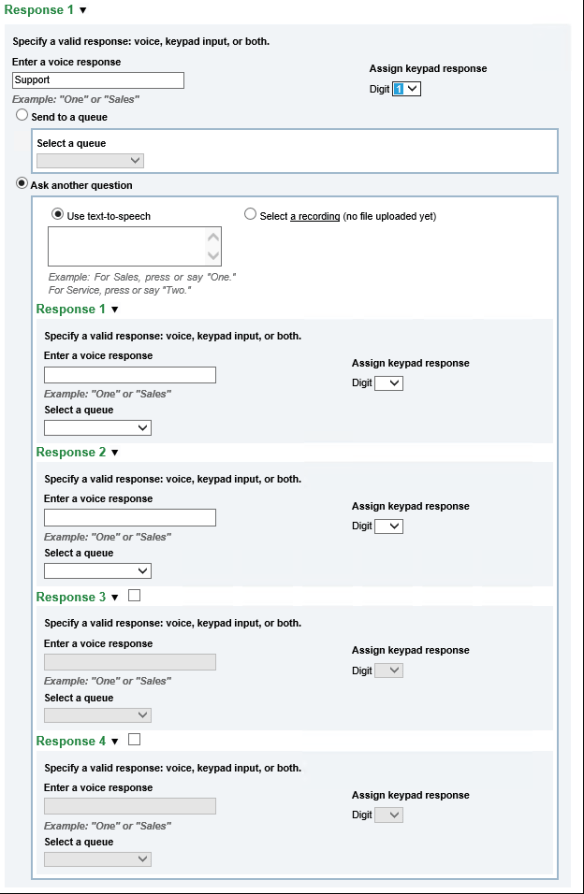

Use the drop-down to indicate what language you want the Response Group service to use for speech recognition and text-to-speech.

Step 3: Configure a Welcome Message

You can choose to play a welcome message to callers, either text-to-speech or something you record. Text-to-speech is great for testing, but not very professional sounding. You can use Audacity or the Windows sound recorder to record a WAV or WMA format greeting, and upload it here. Greetings that you’ve uploaded remain available. You can record all of your greetings at one time, upload them, and then select them as you need them. I’ve seen “closed unexpectedly due to weather” or special holiday greetings used.

Greig has a comprehensive post on audio formats on his blog. I either remember that he’s done this work and refer to it, or I find it in the top results when I do a search.

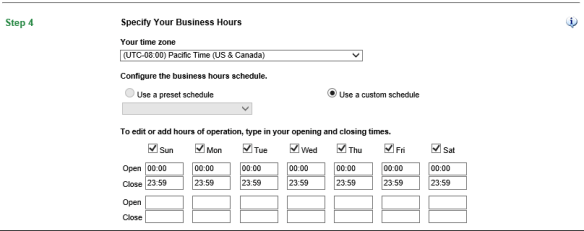

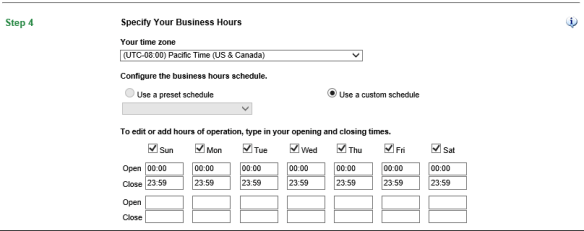

Step 4: Specify Your Business Hours

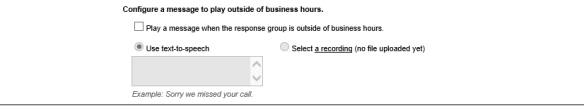

This section lets you configure your timezone and business hours, and set actions for when you are outside of your business hours.

You can define preset schedules via Powershell and select them here, or you can select “use a custom schedule” and enter your hours in the table. Note that opening hours start at the beginning of the minute, and closing hours end at the end of the minute. When you see 00:00 to 23:59 as defaults, that’s a full 24 hour day. You have two open and close times available, which lets you close over lunch time (or nap time).

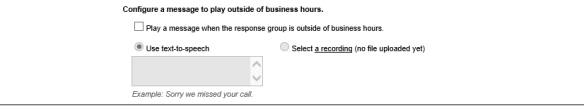

There options for you to play a “sorry, we’re closed” message, these are the same as the greeting.

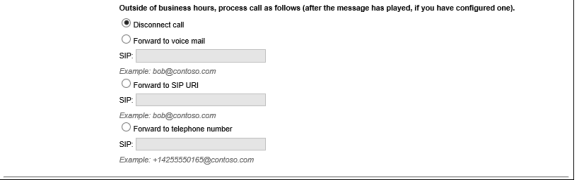

Finally, there are options for how to handle the call after-hours, these are self-explanatory. If you’re going to disconnect the call, please be kind and tell the caller to call back later in the after-hours message.

Step 5: Specify Your Holidays

This option is similar to the after-hours configuration, but is for entire days versus hours or minutes. You configure “holiday sets” via Powershell, but please don’t do this unless you have an irrational love for PowerShell. These two tools the Holiday Set Editor and Lync Tools will save your sanity.

Step 6: Configure a Queue

This is where you pick the Queue that you want this Workflow to deliver calls to. If your Queue isn’t here, you likely started creating or editing the Workflow before the Queue was in the Skype for Business database. You can pick another Queue, save the Workflow, then edit it again to pick the correct Queue. If you haven’t yet created a Queue, you’ll need to start your Workflow configuration again.

Step 7: Configure Music on Hold

Response Groups come with a default music on hold that will play when users are in the Queue. You can configure your own music, by uploading the file here. There are no options for having a voice pop in every few seconds to remind people about how important their call is. If you want to do this, you’ll need to splice together your messages and your music file. Audacity can handle this for you.

I’ve seen a couple of organizations who have a recording of ringback that they use as hold music. This is illegal in some jurisdictions, but it’s also pretty annoying as the caller has no idea that they’ve been Queued unless you have a greeting. Be nice, configure a greeting, and play the default music or another music file suitable for callers to your organization.

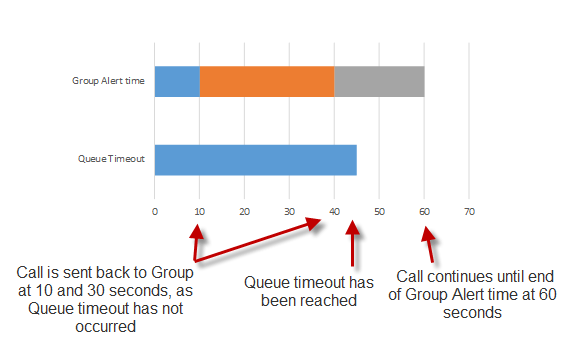

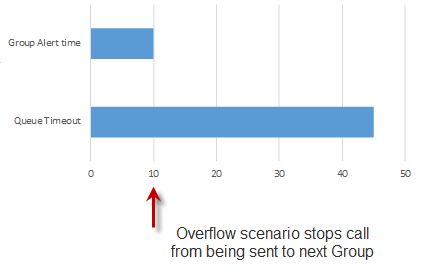

Up next: Response Group Timers and Group Routing Method

I’ve talked a bit already about the two timers in Queues and Groups, as well as the Group Routing Method. I feel that these items need at least one post of their own to get a good feel of how they work together, so that will be covered more in an upcoming post.

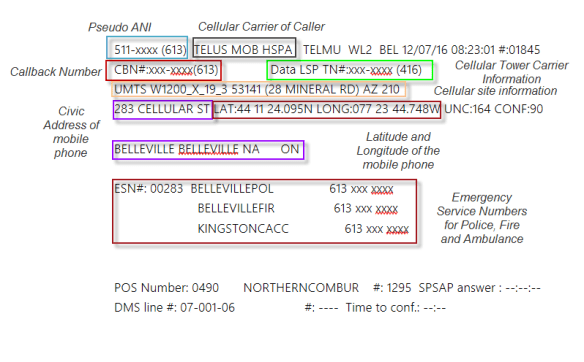

Next up, we’ll have a look at how VoIP Systems can use 3rd party “next generation” services and ugly workarounds to also provide location information to PSAPs.

Next up, we’ll have a look at how VoIP Systems can use 3rd party “next generation” services and ugly workarounds to also provide location information to PSAPs.