When dealing with certificates, people tend to fall into three groups: The first are the security nerds that dream about cryptanalysis and PKI. The second is those people that understand what certificates they need to plug in where, but maybe don’t know the exact differences between things like MD5 and SHA1. The third group are those that follow the steps in the article they’re reading, hoping – sometimes praying – that things just work when they’re finished the last step.

In this post, I’m aiming to help those of you in the hoping/praying group understand a little bit more about what certificates are, why they’re that way, and maybe move you out of the hoping/praying group and into the understanding group. Certificates aren’t typically explained well to the average IT administrator. You either see an explanation of the math behind certificates, or you get vague references to things like the SANs that you’ll need on your certificate, if only you were deploying the exact Lync environment that’s in the blog you’re reading. So, let’s talk about certificates – what they are, how they work, and what different types of certificates exist.

The Basics

Certificates serve two purposes: they identify a device, and they permit encryption.

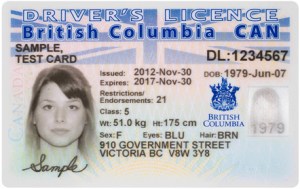

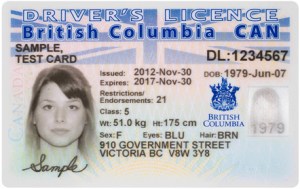

If I were to draw a comparison between a certificate and any non-IT concept or object, I would compare certs to a driver’s license. They’re both issued by some authoritative source, and they are both used to validate your identity.

(Who would name their daughter “Test Card”? I guess someone with a last name of “Sample” might)

A driver’s license will have a photo, and maybe some biometric things like age height, weight, hair colour, eye colour, and a signature. It probably also has an address. It’s also got your name. There’s usually the name of the issuer, an expiry date, and there might be a hologram that you can use to determine if you trust the driver’s license. A certificate has these things, or at least the IT equivalent of them. A certificate has a name (the “Subject Name”, or SN), as well as nicknames, properly know as Subject Alternate Names, or SANs. There’s a field that contains the name of the issuer, location information, and a public key in place of all that biometric stuff.

Trust

The first concept that we need to explore is trust. If I’m trying to order a beer with my dinner, I might need to show ID to prove my age. If I show my driver’s license to the staff, they can easily recognize the license and establish my age. If I’m travelling in Europe, I might run into issues if I show my driver’s license, as the staff may not recognize it, and therefore they don’t trust it. However, it’s likely that I also have my passport with me, and the staff can easily recognize that, and trust it. At a restaurant near my home, the staff trust my driver’s license because it’s in a format that they’re expecting, and they recognize and trust the issuer.

This same concept of trust is how certificates work, too. You can configure a computer or application to trust a certificate, or you can configure the computer or application to trust the certificate issuer, called a Certificate Authority. In the Windows world, Windows has a default list of commonly trusted Certificate Authorities, and updates to this list can be done via Windows Update. You can also add and remove Certificate Authorities from this list manually or via Group Policy or scripting. This is especially important when you deploy your own Certificate Authority on your Domain.

Some applications, like the Firefox browser, choose not to use the Windows list of trusted Certificate Authorities and instead have their own list. Different devices – an iPhone, a Windows Phone, a CX600, or a Galaxy S5 – will all have different lists of which Certificate Authorities they trust.

Public and Private Keys

Now that we’ve got the concept of trust down, let’s get a bit deeper into how certificates work. In the physical world, we have keys and locks, and the key is used to open the lock. The key may or may not be required to secure the lock. In the IT world, we have public keys and private keys. Together, they’re called a key pair. The private key is NEVER given out, and is held on and used by the server identified on the certificate. The public key is ALWAYS given out, and is provided in one of the fields on the certificate.

Encryption

If I want to encrypt something to send to the server, I will use the servers public key to encrypt the information. The server will then use its private key to decrypt the information.

This kind of encryption, called asymmetric encryption, is a bit of a resource hog. There’s another type of encryption, Symmetric Encryption, that uses just one key to encrypt and decrypt, and it’s a much less intensive operation. Since the same key is used for encryption and decryption, you can’t stick in on a certificate that’s publicly available. Instead, the symmetric key is generated using your own private key and the other servers public key, and some math that I’m pretty sure involves dark magic. This keeps the asymmetric key is safe from prying eyes. Symmetric encryption isn’t as strong as asymmetric, so every so often, a new key is generated and replaces the old key.

You can see that a key pair is a little bit different that a physical lock and key. Where a physical key opens the matching lock, the public key and private key in a key pair work as a lock and key in one direction, and a key and lock in the opposite direction.

Signing

Something else that the server can do, is sign something to prove that it’s genuine, kind of like the hologram on the driver’s license. The server performs this signing function with its private key, and you would use the public key to validate the signature. (Our analogy to the physical world falls apart here, and there is no physical-world equivalent of signing with a lock and key).

So, enough about keys. If you’re interested in learning more, I encourage you to have a look at Wikipedia and Bruce Schneier has a great book on cryptography.

Root and Intermediate Certificate Authorities

Okay, so now we know that we have Certificate Authorities that issue certificates, like the motor vehicle office offers drivers licenses. Let’s say that one night, someone breaks into the motor vehicle office, and steals everything that they’d need to make their own drivers licenses. Ouch, that would be pretty bad, right? The driver’s license office might respond by changing the hologram, and if the cards had any kind of chip on them, they’d maybe generate a list of the chips that were on the cards that were stolen, so the stolen drivers licenses could be easily spotted.

Similarly, it would be really bad if someone hacked your Certificate Authority and stole the root certificate. The root certificate is what signs all of the certificates that are issue. The hackers are now able to generate fake certificates that looked valid. Now, all of these fake certificates would be signed by the certificate authority (we talked about signing with keys earlier). The certificate authority would publish something called a Certificate Revocation List, or CRL, that would have the serial number of the certificate that was on the certificate authority. The CRL is usually always accessible via http on a public website. This way anyone can check that validity of a certificate.

In this scenario, the certificate authority would also publish the serial numbers of all of the genuine certificates that were previously issues by the CA with the compromised root certificate. The certificate authority needs to issue a new root certificate, and everybody needs to get a new certificate issued – what a pain! But wait, it gets worse. Windows, your mobile phone, and all kinds of other devices have the root certificate from the Certificate Authority in the list of Certificate Authorities that they trust – and now that root certificate is compromised. There’s no easy way to add the new Certificate Authority root CA into the trust certificates list. You’ll need an update on your device (maybe Windows Update, maybe Apple issues a new iOS version), or you can do in manually. That’s definitely painful.

There is another way to do certificates that prevents this pain, and it’s by using Intermediate Certificates. If a Certificate Authority’s Root Certificate is Papa Bear and a certificate is Baby Bear, an Intermediate Certificate introduces a new generation of bear. The CA Root Certificate becomes Grandpa Bear, the Intermediate Certificate becomes Papa bear, and your certificate is Baby Bear. The Root CA (Papa Bear) can now generate a couple of Intermediate Certificates (Papa Bears). After the Root CA has generated the Intermediate Certificates, the Root Certificate Authority machine is turned off, disconnected from the network, and locked up. This is like Grandpa Bear living under witness protection, or maybe with body guards. The Intermediate Certificates are then what are used to issue your certificate. There are probably multiple intermediate certificates in use by your certificate authority. This is like multiple Papa Bears having lots of Baby Bears.

Now in our theft/hacking scenario, if the CA is hacked and the Intermediate Certificates are stolen, the CA goes through the same CRL process that we saw earlier, except the Root Certificate, powered off and secured, wasn’t compromised. All those devices still trust the Root CA. Replacement Intermediate Certificates are issued, and they in turn generate replacement certificates. Customers (you!) still need to reissue certificates, but you don’t need to worry about updating root CAs on all of your devices.

You can read all about securing a Microsoft Certificate Authority on TechNet. (The TechNet article is free of bear analogies.)

There’s one thing about Intermediate Certificates that I haven’t explained. The Certificate Authority gives you a copy of the Intermediate Certificate when you download your certificate from them. You put the certificate in the “Personal” certificate store, and you put the Intermediate in – you guessed it – the Intermediate Certificate store. Now when anyone needs to interact with your certificate, your server shows them your certificate AND it shows them the intermediate certificate. Think of showing your driver’s license, as well as a “certificate of authenticity” from the motor vehicle office that generated it.

Please, please, make sure that you only put a certificate into the spot where it should go. No Personal (issued to a server, user, or device) certificate in the Intermediate Certification Authorities store, no Root and Intermediate Certificates in the Personal store, etc.. Some applications can choke when they check your certificate store and find the wrong type of certificate in them. Choking isn’t good, as there’s no Heimlich maneuver for servers. You need to be particularly alert when you’re installing a certificate that you’ve just downloaded from a CA. If you just double click the downloaded file, it may stuff your certificate, intermediate certificate, and root certificate all into the Personal Certificates store. If you do double click such a file, run the certificates MMC (the easy way is to run certlm.msc, otherwise open mmc, add the certificate snap-in, and select Local Computer). Open each store, and if you see something in the wrong place, drag it to the correct store. Delete any duplicates – but only after you ensure that the serial numbers match, otherwise the duplicate name with a unique serial number is valid, and may be in use).

You may want to do this clean-up routine on your server’s certificate stores if you’re not sure what state they are in.

Wildcard and Self-Signed Certificates

You probably still have some Lync specific questions like “What is a wildcard certificate, and why doesn’t Lync like them”.

We’ve already said that a certificate is your driver’s license with your picture, name, age, height, weight, and signature. This is great for validating your identity, but what about a situation where you also need to validate who you’re talking too? That’s often the case when you have two servers that need to communicate, like your Edge and your Front-End, or maybe your Mediation Server and your Exchange UM server. In a case like this, the servers need to show each other their certificates. When two servers use their certificates to validate their identity and encrypt traffic, it’s called Mutual Transport Layer Security, Mutual TLS, or just MTLS.

This is really different from plain TLS, which isn’t mutual at all. TLS secures traffic both ways, but only proves the identity of one of the parties in the conversation. You use TLS when you browse to a web server over HTTPS, like your bank. The server has a certificate, but your client doesn’t. Depending on the server and what you’re doing on it, you might have to validate your identity with a username and password, or you might have some form of two-factor authentication.

So, a wildcard cert looks like this:

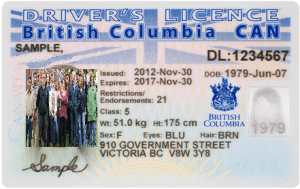

If we were to compare a wildcard certificate to a form of “wildcard” driver’s license, it would have no first name, no height, weight, age or signature, and instead of your mugshot, it would have that really bad photo from your Sample family reunion last summer where your crazy uncle Dave looked like he was ready to pass out. And that would allow anyone who was at that reunion, who shares your last name, to drive. Yes, even your crazy uncle Dave. Seriously – who would think that this kind of driver’s license is a good idea?

Wildcard seem like a pretty silly thing. Are they completely useless? Well, no. They do serve a valuable function, and that is to provide a low cost certificate that you can use on a variety of your devices to ensure traffic is encrypted. A Bank would NEVER use a wildcard cert. Google uses wildcard certs where they just need to ensure encryption, such as when you search. However, Google uses a full Subject Name on certificates for things like Gmail, where you need to validate the server’s identity.

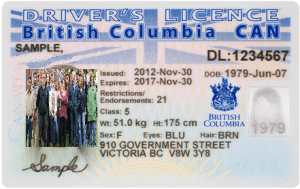

Another type of certificate is a “self-signed” certificate. These show up in web interfaces on routers and switches, and they’re also used in Exchange when that’s installed. Putting a self-signed certificate on your server is like your server saying “hey, I’m your server! Here’s my certificate that I issued to myself! Trust me!!!”. This is a crazy, crazy concept. Here is the driver’s license equivalent of a self-signed certificate:

That’s right, your 6 year old cousin Megan (she was only three at the family reunion where the picture for your wildcard certificate was taken) drew up her own driver’s license! Hand her the keys to the Prius and stand back everyone! 6 year old Megan drive!

No, she can’t. She probably can’t even see out the windshield or reach the peddles. The concept of Megan drawing her own driver’s license making her able to drive and use it as a form of ID is silly, and only her mom, dad, and her stuffed unicorn would ever trust it as a form of identification.

Self-signed certs, by default, are only ever trusted by the server that issued the certificate to itself. If you want your computer to trust it, you have to add that certificate to the Personal store of your computer. You shouldn’t add the self-signed certificate to the Trusted Root Certificate Authorities store, because it’s not a Certificate Authority. And, just because you can trust a self-signed certificate, that doesn’t mean that you should. Self-signed certificates are great for your lab, but not much more. If you’re thinking of using a self-signed certificate in a production environment, you should consider why you need a certificate in the first place. If you have reason to need a certificate, set up Active Directory Certificate Services. If you don’t need a certificate, save yourself the trouble and just use HTTP or whatever protocol gets the job done without the certificate.